Reflections on a Writer’s Return to Mexico 100 Years Later

By Manuela Gomez Rhine

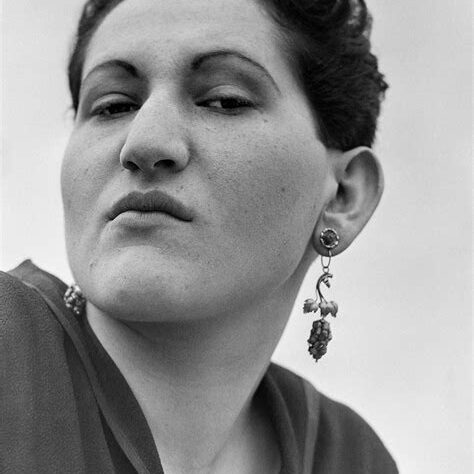

Anita Brenner was not a conventional beauty. Nor was she a conventional thinker. She clearly had a mind and look of her own as evidenced in this iconic 1926 photograph taken by Tina Modotti in Mexico. Though at the time only 21 years old, Brenner appears regal, confident and self aware.

By this point in her life, Brenner had embraced her identity as a Jewish Mexican-American woman, even though her Jewish heritage and Mexican background brought scorn while she lived in the United States from the ages of eleven to eighteen. In 1923, painful discrimination prompted Brenner to flee Texas and return to her native Mexico. By 1924 she was working there as a journalist and writer.

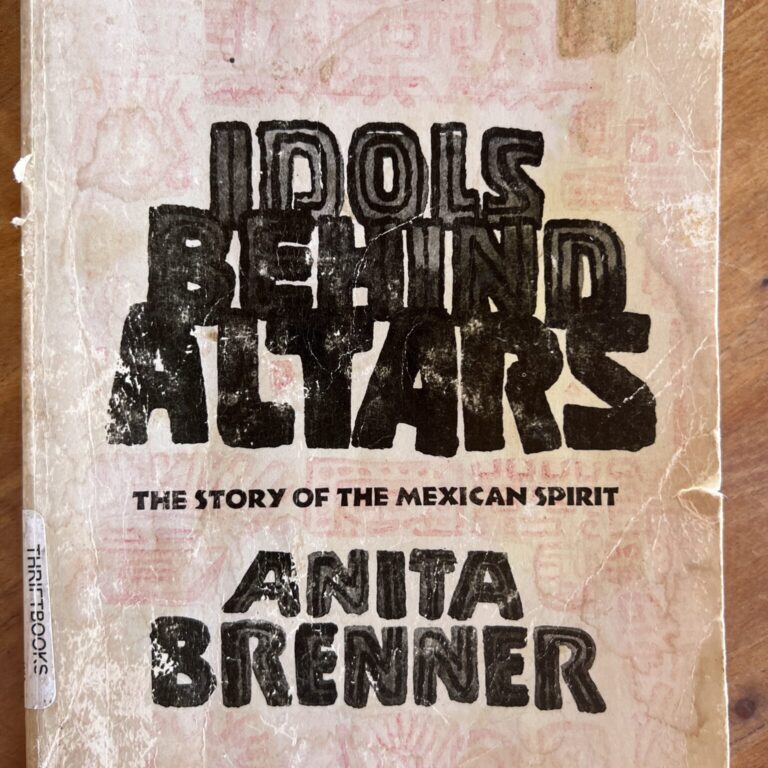

I stumbled upon Anita Brenner while researching Mexican history. I ordered and read her 1929 book Idols Behind Altars in which she writes about the Mexican spirit as related to its indigenous history, customs, religion and art. A literary force who went on to write many books, Brenner demonstrates in Idols Behind Altars her innate understanding of Mexico's beautiful and tragic soul. About the Mexican spirit she wrote:

The need to live, creating with materials; the need to set in spiritual order, the physical world; the sense of fitness–these are components of an artist's passion and these are the Mexican integrity. That is why Mexico cannot be measured by standards other than its own, which are like those of a picture and why only as artists can Mexicans be intelligible.

I celebrate Anita Brenner as our latest Mexicanista not merely for her work and considerable legacy, but for the vigorous way she pursued her visionary ideas. When Brenner burst onto Mexico City's post Revolution art scene at age 18, a hundred years ago, she did so with unapologetic boldness and moxie. Consider:

1. After experiencing antisemitism and discrimination in the U.S., Brenner did not shrink back but embraced her identity.

In 1923, after living in Texas for seven years, 18-year-old Brenner persuaded her parents to let her to return to Mexico. (The family fled Aguacalientes in 1916 to escape turmoil from the Mexican Revolution.) To leave behind her family and travel alone toward an unknown future most certainly took courage. But Brenner refused to live among people who disparaged her heritage. After completing her freshman year at the University of Texas, Brenner boarded a train to her destiny.

2. She found people who matched her own intellect, creativity and ambition, and charged into their orbit with the belief that she belong among other dazzling people.

When Brenner arrived in Mexico City from San Antonio, she discovered a vibrant scene forming around the Mexican Muralist movement. Brenner wasted no time forging friendships with artists, writers, intellectuals, and social and political activists, including Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Tina Mondotti and Edward Weston. Anita nurtured these relationships. She found mentors and created projects with colleagues. She worked hard and generated her own opportunities. In 1926, for example, she commissioned Modotti and Weston to travel with her and take photos as she researched Mexico's decorative arts.

3. Brenner embraced who she was and what she loved, and shared these aspects with audiences around the world.

As a Mexican-American living amidst a creative revolution, Brenner also saw an opportunity to write in English about the art, culture, and history of Mexico that she loved, and import this information to foreign readers.

Whether Brenner pursued these paths from an altruistic desire to build cultural bridges, or she developed a savvy marketing perspective of how to get her foot in the door, what does it matter? She created a life with purpose and left behind a rich legacy.

4. She developed the skills she needed to achieve her visions and goals.

As a Jew in Mexico during a time when European Jews were immigrating there in high numbers, Brenner was compelled, based on her own feelings of acceptance, to promote Mexico as a destination for their migration. Brenner became a self-taught journalist. She pitched editors story ideas and began writing articles that painted a positive image of Mexico as a safe-haven for Jews for both Mexican and American journals and newspapers.

Who Was Anita Brenner?

Anita Brenner was born in 1905 to Jewish-Baltic immigrant parents from Latvia who first settled in Mexico. In 1916 the family fled Aguascalientes to escape the violence of the Mexican Revolution. In Texas, Anita was scorned for being different as a Jew and Mexican. At 18 she begged her parents to let her finish college at Mexico City’s National University. I late 1923 Anita boarded a train and traveled to Mexico City on her own.

Part of a circle of Mexican artists and intellectuals drawn to Mexico City after the country's revolutionary war, Brenner helped its founder, Frances Toor, launch in 1925 the influential magazine Mexican Folkways. She worked as a translator and research assistant for the Mexican anthropology Manuel Gamio. She collaborated with the painter Jean Charlot on a series of articles and book projects chronicling the Mexican muralist movement. Anita absorbed many lessons from her many mentors who gave her educations in photography, writing, archeology, history and art-making.

As part of her lifelong quest to promote Mexican culture to an American audience. Anita moved to New York in 1925. In 1929 she published her seminal work, Idols Behind Altars. The book's eclectic view of Mexico’s indigenous traditions and contemporary artists was a success.

By the 1930s, Brenner was one of the earliest interpreters of Mexican modern art in the United States, and one of the main promoters of what historian Helen Delpar called “the enormous vogue of things Mexican,” which reached its peak in the Depression years. Throughout her career, Anita Brenner's writings profoundly influenced the international embrace of the Mexican Renaissance, a term she herself coined.

She received a PHD in anthropology from Columbia University in 1934. She was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for the study of Aztec art in Europe and Mexico. From 1955 to 1971 she ran the magazine Mexico/This Month. It worked to improve social and business relations between Mexico and the U.S. by promoting travel, investment and retirement in Mexico. In later years she ran an agricultural farm in Aguacalientes.

Anita Brenner died in an automobile accident in Mexico in 1974. She was survived by a son and daughter.

Post Revolution Mexico City

After the Mexican Revolution ended in 1921, the country’s capital began to evolve as an important center of indigenous politics, art and philosophy. US and European artists, writers, folklorists and intellectuals were captured by the city’s counter culture and emerging artistic scene. Exiled revolutionaries, émigrés, refugees, revolutionaries and dreamers flocked to Mexico City throughout the 1920s.

An influx of Jews to Mexico in the 1920s

Between 1917 and 1920 Jews began to arrive in Mexico from Russia, Poland, Lithuania, the Balkans and the Middle East. The rate increased in 1921 when the United States imposed quotas on its immigration and Jews were forced to find another country to call home. Ten thousand arrived from Eastern Europe to the port of Veracruz at the invitation of President Plutarco Elías Calles. In 1924-25 the mass arrival of Jewish migrants to Mexican shores grew even more. Jewish organizations such as the Comité de Damas and North American B'nai B'rith were formed to help the new arrivals adapt. Anita Brenner’s parents and older siblings were part of a Jewish diaspora, emigrants who arrived in Mexico and settled in Aguascalientes.