Why I Started Mexicanista & How Tia Elisa Played a Role.

Hola, my name is Manuela Gomez Rhine. I am editor and founder of Mexicanista, a new online publication to highlight and celebrate women of Mexican heritage, nationality or connection, and their contributions to culture, beauty, truth, and society.

The first step that led me on this path began with early family trips from our home in Los Angeles to Mexico, and the fondness I developed for my Tia Elisa who we always visted. Elisa was the first beautiful, strong, interesting and self-directed Mexican women I encountered, a role model who planted seeds that sprouted ideas of who I could be.

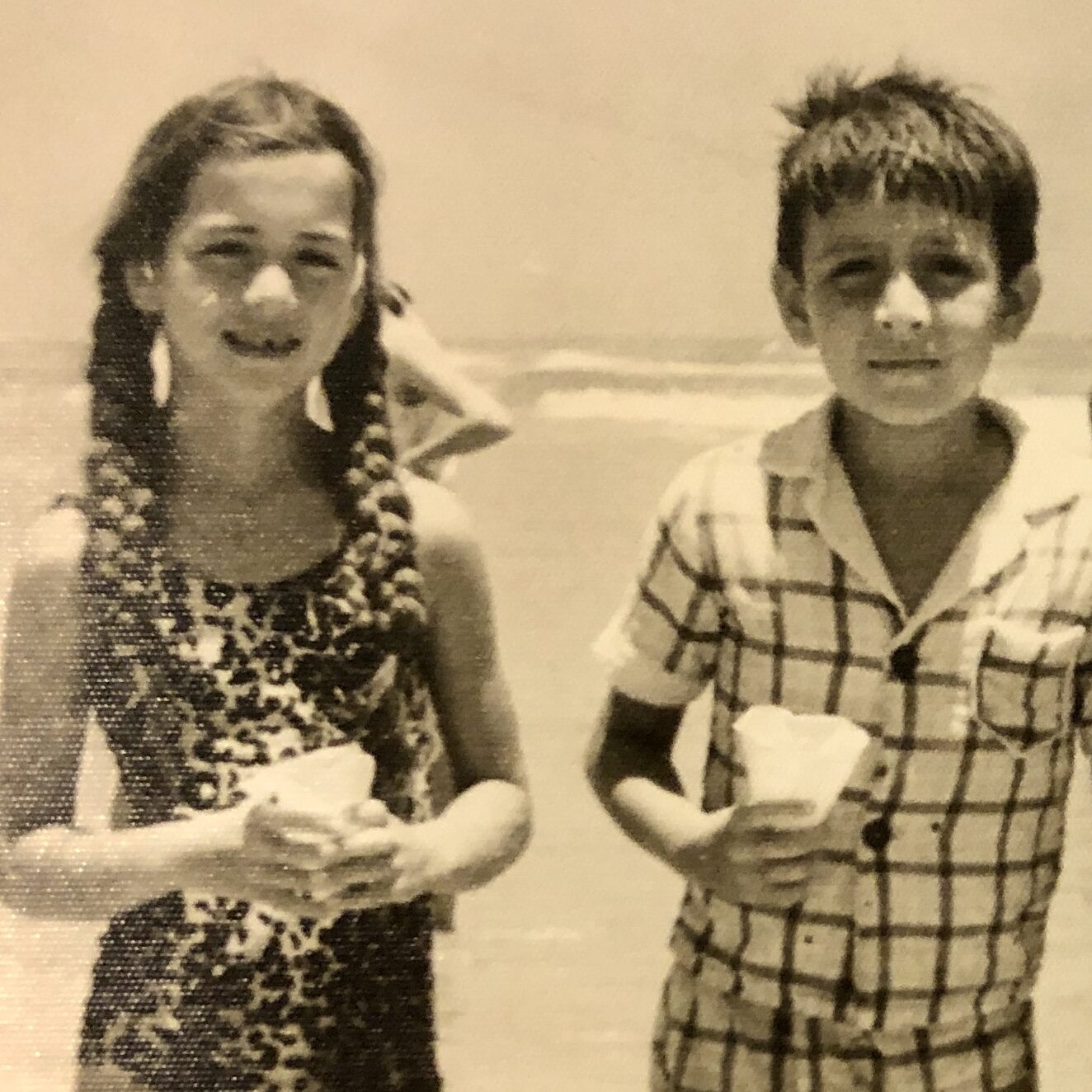

Of my father Manuel’s four siblings, Elisa was his favorite. She was always around during our visits to Tampico, Tamaulipus, where she and Papa were raised, and Mexico City, where she worked as a lawyer for Pemex, Mexico’s state-owned petroleum company. A single mother to her only child, Moises, she had once had a husband, but no one ever mentioned him. I didn’t realize then, in the 1960s and 1970s, just how modern and independent Elisa was. With her pencil skirts, short bobbed hair, and warm smile, Elisa, kind and patient, doted on me during our visits. She called me “Traudita” (I was named Traude for my mother) and seemed to regard me as the most special little girl in the world.

Elisa and Moises lived in a modest ground-floor apartment on Avendia Ixtaccihuatl in Mexico City’s La Condesa neighborhood. It was a moment’s walk through Parque Espana to Sanborn’s Restaurant, where we often ate and where my father bought me and Moises comic books from the gift shop. The bright and bustling restaurant with its ice cream sundaes and hamburgers, gift shop stocked with magazines, souvenirs and candy, was kiddie paradise.

I grew up in Monterey Park, California, a town adjacent to East Los Angeles, a largely Mexican-American community. Papa worked as a medical doctor at a clinic in East LA. His patients were mostly Spanish speakers. I was surrounded by Latin culture. It was home.

While studying journalism at San Francisco State University in the 1980s I read biographies of Frida Kahlo and studied the arresting documentary work of female photographers Lola Alvarez Bravo and Graciela Iturbide. Over time I watched actor Maria Felix command the silver screen and activist Dolores Huerta speak truth to power. I listened as Lila Down unleashed a ballad. Throughout my life, these women and others have nurtured my spirit and soul, passion, creativity, talent, and views.

Now that I’ve entered my sixth decade on planet Earth, after a career as a print and online journalist, an editor, writer and novelist, it seems a worthy use of my skills and time to celebrate women, both famous and unknown, prominent and overlooked, to bear witness to the importance of their lives, big and small. Yes, women of notable achievements, but also the Tia Elisas of the world. The unsung and uncelebrated.

Elisa died in 2012 at the age of 93. Her ashes are interred at Iglesia San Ignacio de Loyola nearby her last apartment in the Mexico City neighborhood of Polanco. I was touched that Moises and his family waited until I arrived six months after her death so we could inter the ashes together.

It was on that trip that I asked Moises about the old apartment in La Condesa where we had all stayed together as kids, when our parents were still alive and we ate Sanborn’s ice cream sundaes and read Archie comic books in the glow of their love and care.

He wrote down Edificio La Princesa, Avendia Ixtlaccihuatl on a scrap of paper. I walked alone to La Condesa and wandered the neighborhood, but could not find the building. Nothing looked familiar. I left disappointed.

Then, on a recent trip a decade later, I decided to try again and, as if Elisa were calling, I walked straight to the magnificent front door of the Edificio Princesa, an art deco wonder that I hadn’t seen in fifty years. As I stood before the elegant vintage stained-glass entrance, I first imagined Carrie Bradshaw flouncing through the door. So stylish was the building and neighborhood that if "Sex and the City" was set in CDMX, Carrie would live in Edifico Princesa. But then I saw lovely Tia Elisa stepping over the transom, holding hands with both me and Moises as we headed off Sanborns.

The Allure of Oaxaca, Mexico, and Why I Call it Home

I live in an adobe house at the top of a steep hill just outside of Oaxaca City. The journey that has brought my husband, Michael, and me to build our home started in 2006. We chanced upon the hillside lot in Ejido Guadalupe Victoria during a trip to Southern Mexico.

We knew it was madness to buy a lot more than 2000 miles away from our home in Los Angeles, with money we really didn’t have, but I had always imagined myself living in Mexico. That morning as we stood on the property’s arid red earth, gazing at the view to Oaxaca City, a sensation overwhelmed me. A voice whispered, “This is home. ”

The lot sat empty for ten years. We lived our California lives, working in Los Angeles and raising our daughter, Ramona. During that decade we made occasional visits. In 2013 I came more often as my mother was dying of multiple myeloma, and the Thalidomide prescribed by the oncologist was, in Mexico, a fraction of the US price. On these trips, after buying all the Thalidomide the pharmacy allowed, I would hike up our hill and walk across the lot that abutted a scrubby land preserve dotted with native white-flowered Cazahuate trees and tall golden grasses. I would sit on the hillside for hours watching birds of prey soar and dive.

In 2016, when Ramona went to college, we had some time and money. Our contractor broke ground on a simple one-story house constructed from adobe bricks and sliding glass doors. High ceilinged with concrete floors, it is simple yet elegant to match the simple yet elegant life I imagined for ourselves. Construction spanned several years. We built when we had money.

Waited when we didn’t. All the while the slow forming of a house matched the slow forming of my new sense of identity.

As Michael and I traveled back and forth between the two culture I was challenged to probe more deeply my sense of identity about what it means to be a first-generation American woman born to a Mexican father and German mother. During longer stays in Mexico, I began to ask In what ways was I American? Mexican? German? How was I perceived by Mexican friends? In what ways did my American characteristics come into sharper relief? How was my love for Mexican culture defined?

Now as I live in our Oaxaca home I am nurtured by the natural beauty that extends all around our hillside. To the east I am gifted with a view of the majestic Sierra Madre Mountains that are often shrouded in fog like a voluptuous woman draped in chiffon scarves. The open sky provides a daily show of golden sunrises, afternoon thunderstorms electrified by lightning, double rainbows, rising moons and scuttling clouds. At an altitude of 5,102 feet, we live within a cloud forest.

Oaxaca City itself unfolds two miles below our rural neighborhood. From our living room window, we can see the baseball stadium. Its neon sign blinks red and blue during baseball season when the Guerreros of the Mexican league swing their bats to cheering crowds.

Often I stay in Oaxaca by myself for months at a time. Coexisting with the spiders and scorpions, dogs and cats that wander into the yard and house. Every morning a boy herds his cows up the hill. As a writer, I cherish solitude. Nights here in particular carry a profound silence. It’s within this stillness that a whispering voice asks me, Why did you come? What are you searching for?

In the light of day I can give a hundred different answers as to why I chose to make this place my Mexican home. But in the stillness of night, I know at my deepest level I am searching for my Papa. I’m trying to reconnect to his spirit and love that nurtured my soul throughout my childhood and that was extinguished that rainy April day in 1988, when he was killed in an accident in downtown Los Angeles.

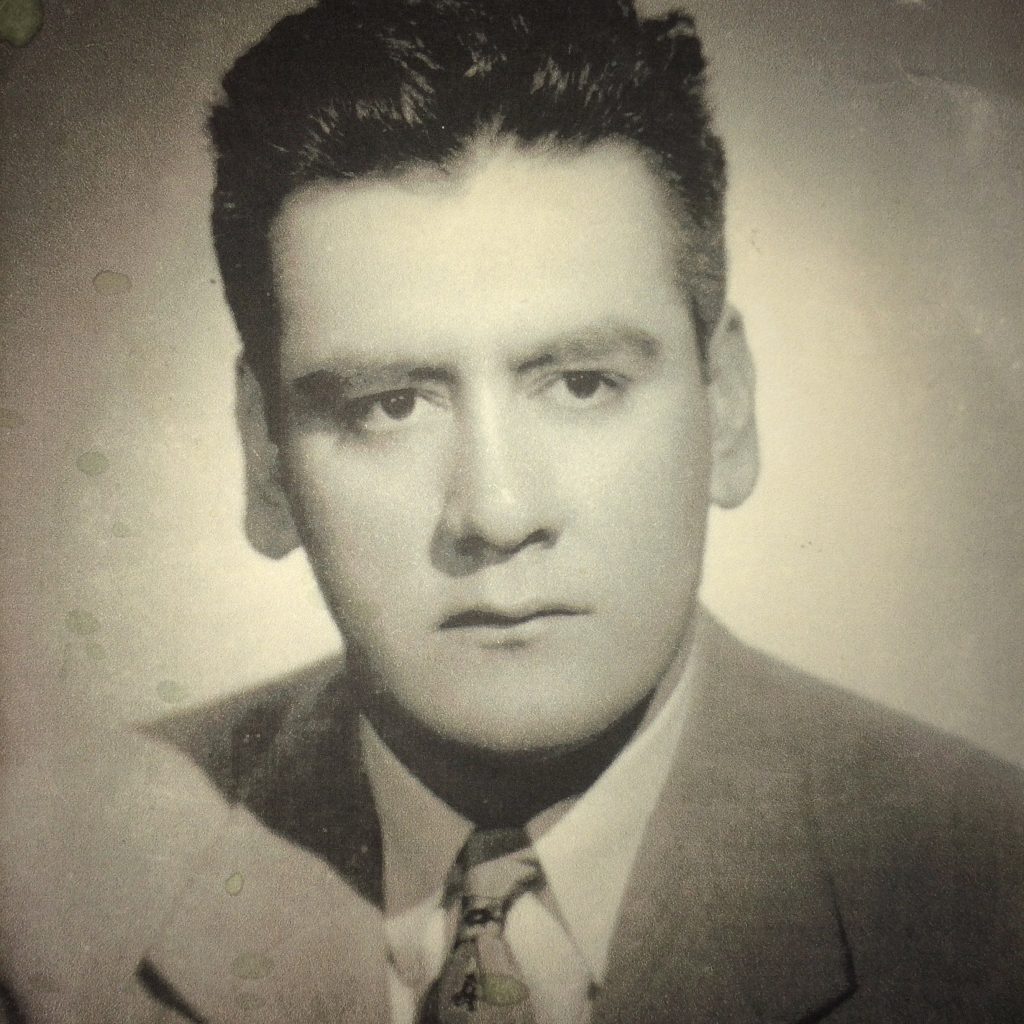

It was my father, Dr. Manuel Gomez, who gave me Mexico and the ability to be naturalized Mexican through my birthright as his daughter.

Papa was born in 1921 on Mexico’s Gulf Coast in the port city of Tampico, 360 miles northeast of Oaxaca. The first time I ever came to Mexico was in the 1960s to visit my paternal family. My mother drove my brother and sister and me down in her Country Squire Station wagon on a weeks-long journey.

We stayed the entire summer. Papa would join us when he took vacation from his medical clinic in East Los Angeles. Every morning our family, and often my cousin Moises, would take the street car to the white sanded beaches. Together then we would swim in the warm gulf coast water in which my ancestors bathed. I swam with their ghosts.

My story is about Germany too. My parents, both immigrants, met in New York City in 1956. As a child I went to stay with my mother family in Berlin, a place to which I am deeply bonded. But this bond is built on a legacy of war trauma. My mother Traude and her entire family lived through World War II and the Russian invasion of Berlin. Traude always said that Germany only gave her bombs and hunger. She did her best to leave them behind by becoming American and living in the land of orange groves and sunshine. Yet her trauma never dissipated.

It moved into her bones as cancer and eventually pulverized them. I know the immigrant experience isn’t always easy. People leave places for difficult reasons. Sometimes not by choice. Sometimes never to return. Sometimes they are forever haunted by what they left behind.

My father's experience of moving to a new country for better opportunities filled him with a lifetime of longing and I believe regret. I always sensed that Manuel missed Mexico terribly. He visited every year and when in Los Angeles (which is Mexico in so many ways), he socialized with Mexican friends, ate Mexican food, listened to his Mexican records on Sunday afternoons. After he was killed by a bus in 1988, we brought him back to Tampico, and buried him in the Trinidad Cemetery. I dedicate Mexicanista to my father Manuel and to all my ancestors who followed their vision and passion to create a better, more beautiful world.

Furry Tails of Oaxaca: Animal rescuers I know in Los Angeles (and I know many) say the area is one of the worst in the US for unwanted cats and dogs (for reasons I don’t have space to enumerate here). The LA shelters are sadly filled with an excess of Chihuahuas and for most of my adult life I have rescued and fostered these special little dogs. Mexico, on the other hand, has more street dogs than any other country in Latin America. I don’t know which is worse - animals warehoused in cages or those roaming the street.

I was intrigued in 2022 when a new friend in Oaxaca City, Mary Maier, asked me to join her efforts to start a nonprofit that would fundraise to cover expenses of volunteers and vets who are already organizing sterilization campaigns in cities and pueblos throughout Oaxaca. Furry Tails of Oaxaca is now in operation. We have already raised funds to sterilize hundreds of animals. Spaying and neutering both here and in the US is the main way we can prevent more unwanted animals. As it costs about 250 pesos (around $15 dollars, depending on exchange rate) to sterilize one cat or dog, the investment is minimal compared to the benefit. Find out more about our work at www.furrytailsofoaxaca.org