The image of Ramona, as interpreted by artists, directors, publishers, and promoters, has endured within California's visual language. With the official publication of The Palm Tree Chronicles, in which Ramona plays a starring role, we explore the literary heroine's legacy to our Golden State.

By Manuela Gomez Rhine

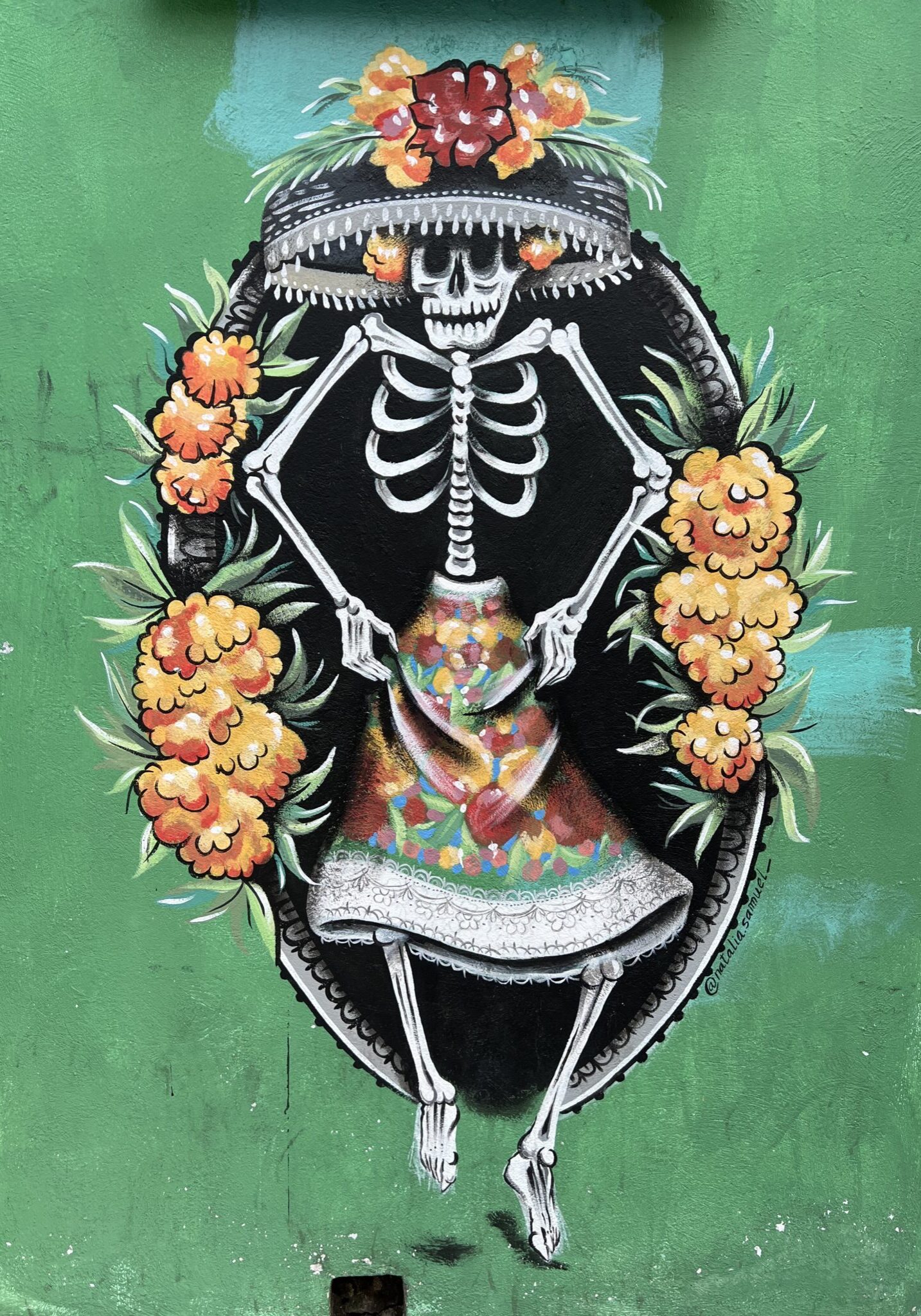

For 140 years, Ramona has reigned as one of California's most ubiquitous celebrities. Her name graces street signs, schools, towns, and highways throughout the SoCal region. Her dark-haired beauty has been depicted in movies and on stage. Since she first sprung from the pages of Helen Hunt Jackson's 1884 best-selling, myth-making novel, Ramona has come to symbolize the promise and potential of the California dream. She embodies the romance of the Mexican Ranchos. The fragrance of orange blossoms across a citrus grove.

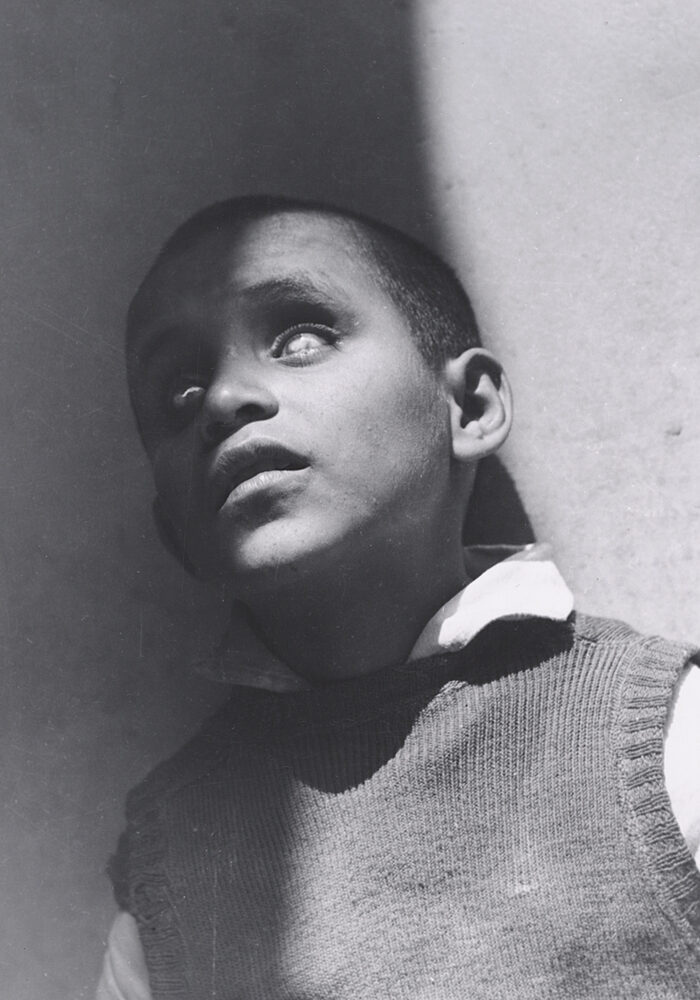

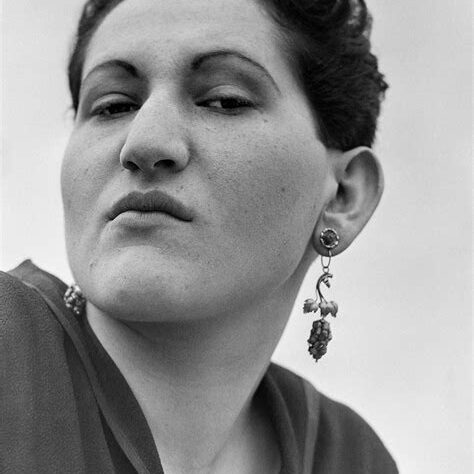

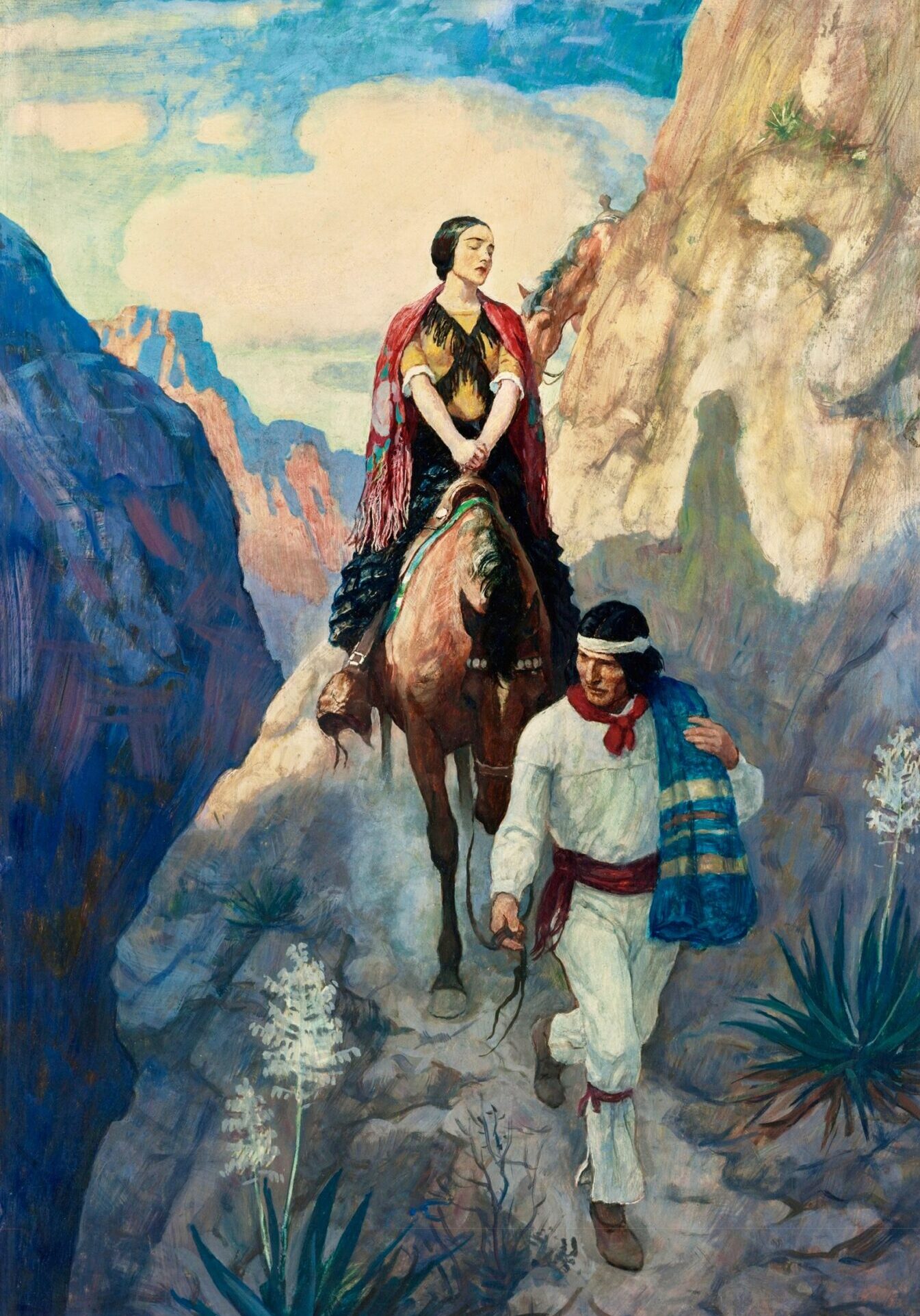

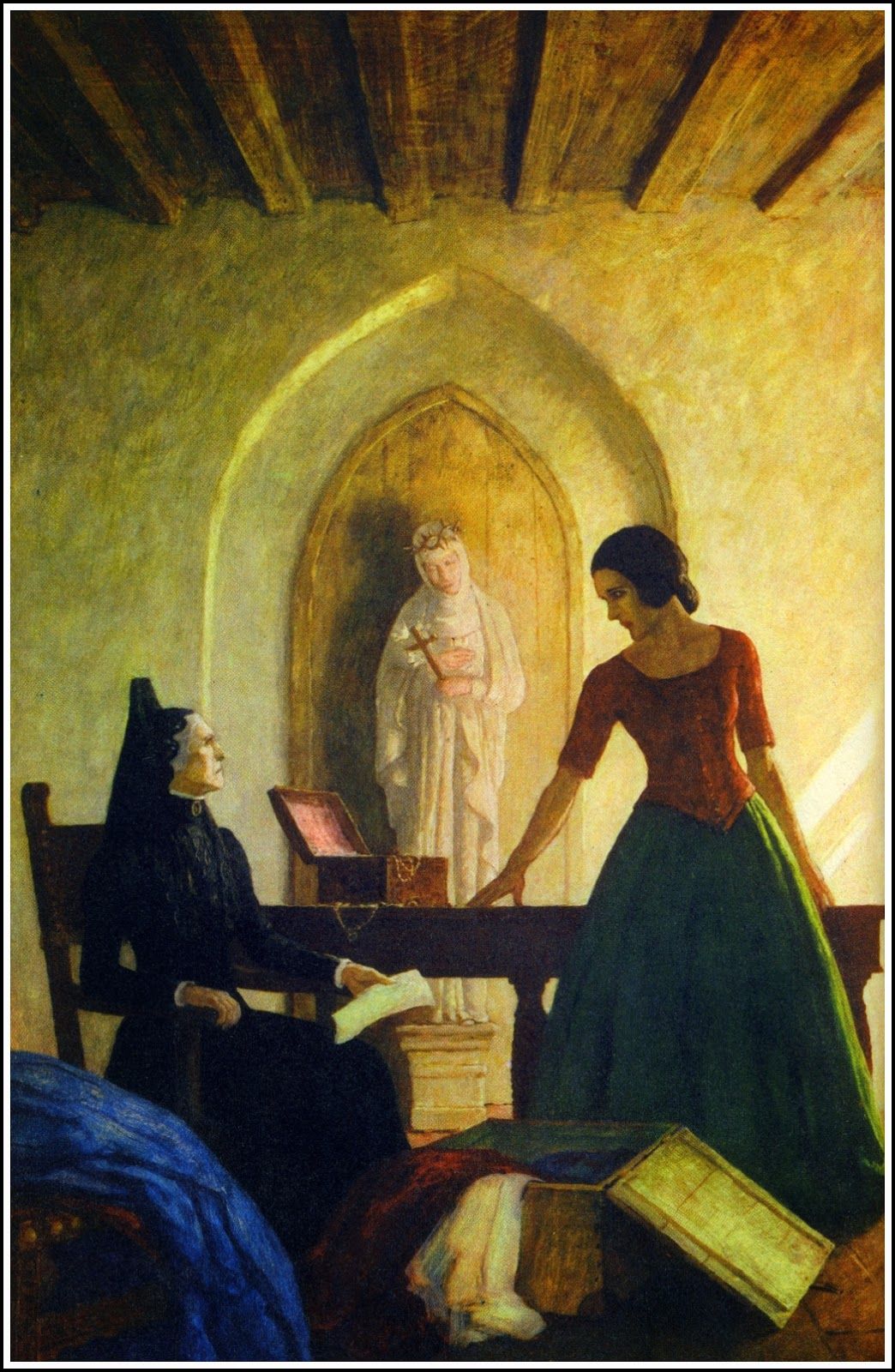

Of the many versions of Ramona featured on numerous book covers, my favorite interpretation comes from N.C. Wyeth (1882 -1945). Publisher Little, Brown and Co. commissioned this work (left), from the American artist to illustrate its 1939 novel edition. Read more about Wyeth at the National Museum of American Illustration web site.

At the time, Wyeth created four cover renditions for the publisher, including the illustration (left) Ramona with her Guardian. (The original illustration was discovered in 2017 in a New Hampshire thriftstore and purchased for four dollars. Read more here.)

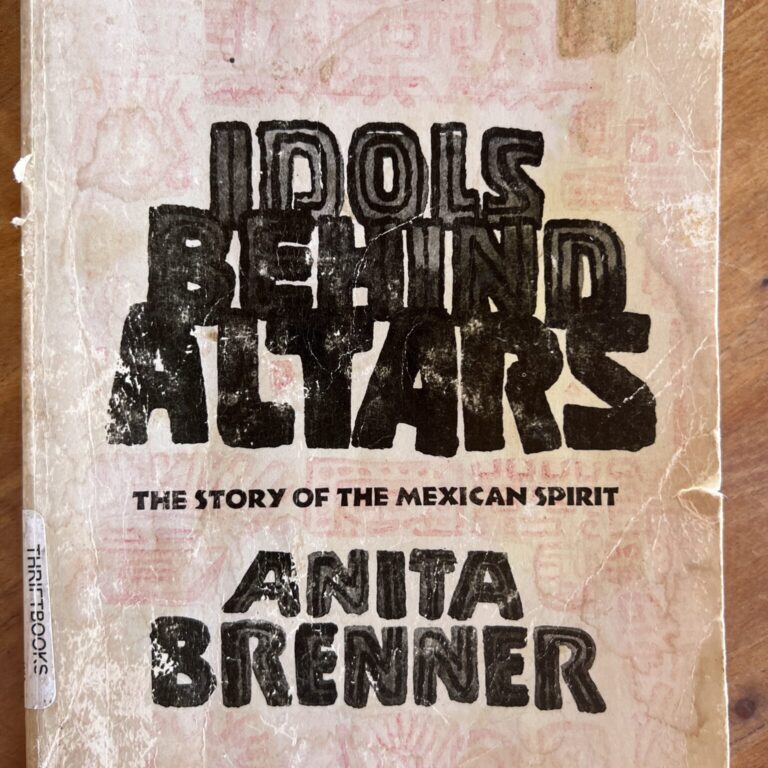

Alas, Ramona, an orphan of Scottish and Native American roots, is also a dark reminder of California's brutal mistreatment of Native Americans, first by Franciscans in the Spanish Missions (1769 - 1833), then as forced laborers within the Mexican Rancho system. Things worsened when settlers arrived in the west with U.S. Government land grants declaring them rightful owners of the Indian's ancestral homelands.

Helen Hunt Jackson's foremost goal in writing Ramona, was to educate readers regarding the genocidal treatment of Native Indians. The love story was merely a vehicle through which to make the facts more palatable. But publishers, film directors, and theatrical productions focused on the love story aspect. Ramona's ill-fated love affair with the Indian Alessandro was simply more captivating than the tragic plight of the native people and the loss of their land. Readers embraced the beautiful and virtuous Ramona. They were entranced by the writer's descriptions of California's natural landscape. Ramona was a best-seller not for its message of social justice, but because the romance of Ramona and Alessandro and the beauty of California kept readers turning pages.

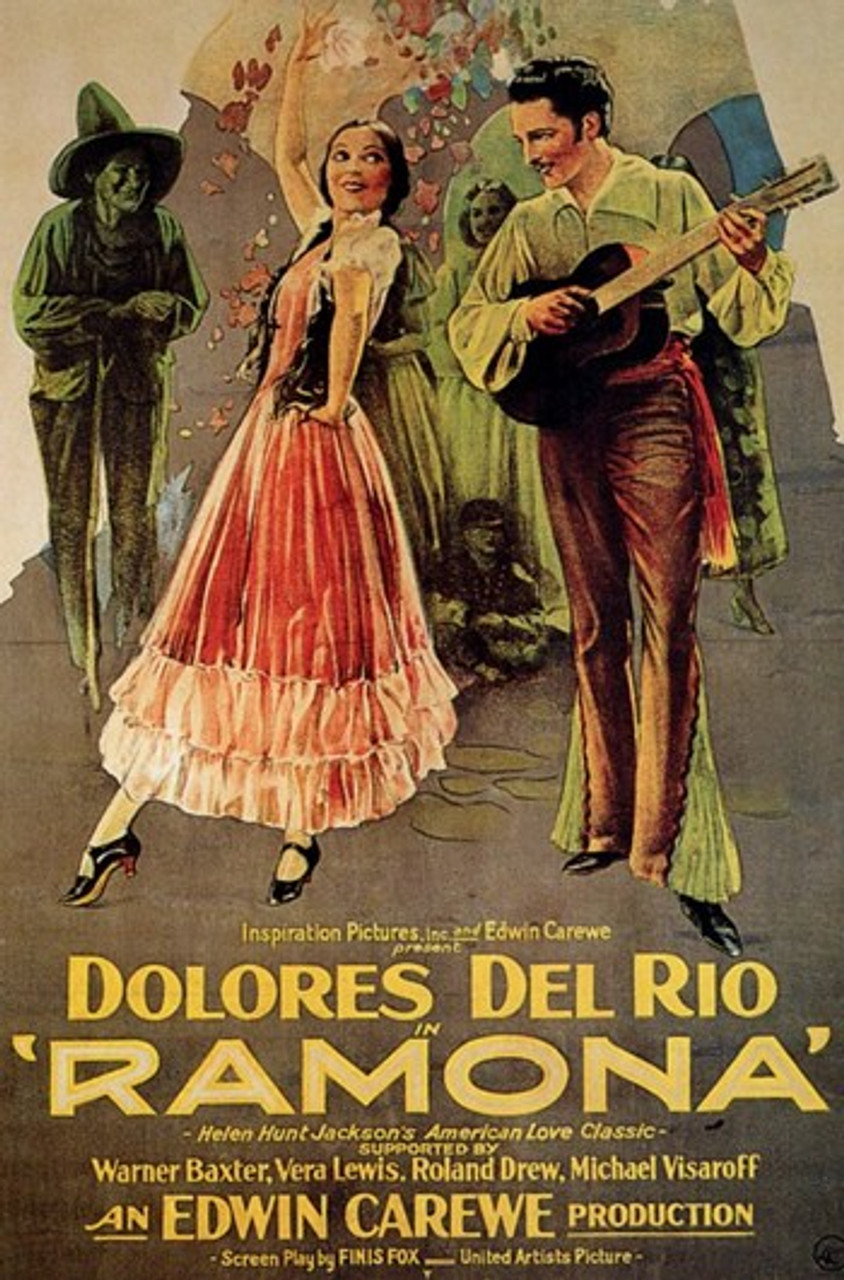

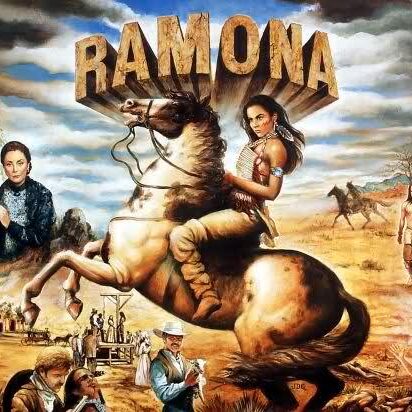

Since the publication of Ramona in 1885, numerous book editions, movies and plays have been released. Ramona has been brought to life by silent screen actor Mary Pickford, Dolores Del Rio, and Loretta Young. Below are several depictions of Ramona for the stage, film, and television: